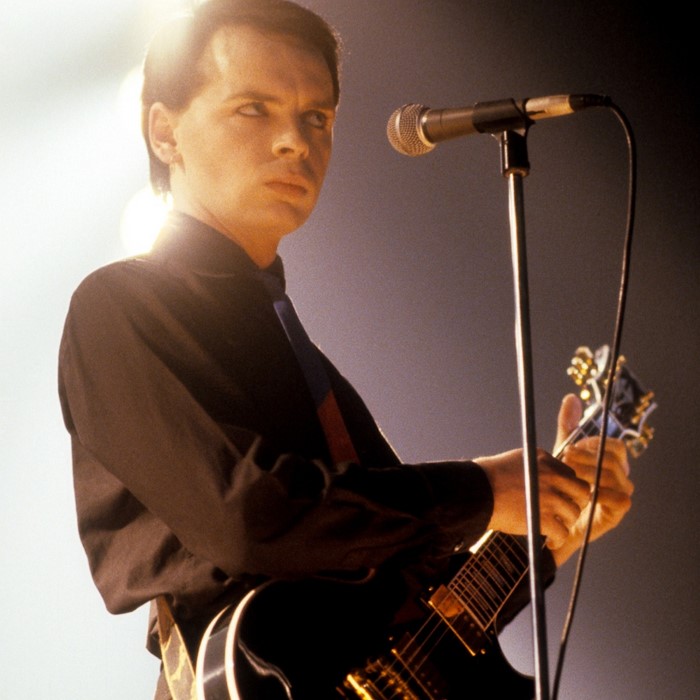

Gary Numan

📅 1977

🌍 Hammersmith, England, UK

🎵 Rock

One of the founding fathers of synth pop, Gary Numan’s influence extends far beyond his lone American hit, “Cars,” which still stands as one of the defining new wave singles. That seminal track helped usher in the synthpop era on both sides of the Atlantic, especially his native England, where he was a genuine pop star and consistent hitmaker during the early ’80s. Even after new wave had petered out, Numan’s influence continued to make itself felt; his dark, paranoid vision, theatrically icy alien persona, and clinical, robotic sound were echoed strongly in the work of many goth rock and (especially) industrial artists to come. For his part, Numan just kept on recording, and by the late ’90s, he’d become a hip name to drop; prominent alt-rock bands covered his hits in concert, and a goth-flavored brand of industrial dance christened darkwave looked to him as its mentor.

Numan was born Gary Anthony James Webb on March 8, 1958, in Hammersmith, West London, UK. A shy child, music brought him out of his shell; he began playing guitar in his early teens and played in several short-lived bands. Inspired by the amateurism of the punk movement, he joined a punk group called “The Lasers” in 1976. The following year, he and bassist Paul Gardiner split off to form a new group, dubbed “Tubeway Army”, with drummer Bob Simmonds; they recorded a couple of singles under futuristic pseudonyms (Valerium , Scarlett, and Rael, respectively) that attempted to match their new interest in synthesizers. Scrapping that idea, Webb rechristened himself Gary Numan and replaced Simmonds with his uncle Jess Lidyard. Thus constituted, “Tubeway Army” cut a set of “punk-meets-Kraftwerk” demos for Beggars Banquet in early 1978, which were released several years later as “The Plan”. That summer, Numan sang a TV commercial jingle for jeans, and toward the end of the year the group’s debut album, “Tubeway Army”, appeared. Chiefly influenced by “Kraftwerk” and David Bowie’s Berlin-era collaborations with Brian Eno, the album also displayed Numan’s fascination with the electronic, experimental side of glam (”Roxy Music”, “Ultravox!”) and krautrock (”Can”), as well as science fiction writer Philip K. Dick.

The group’s second album, “Replicas”, was released in early 1979. Its accompanying single, “Are ‘Friends’ Electric?”, was a left-field smash, topping the UK charts and sending “Replicas” to number one on the album listings as well. The record also included “Down In The Park”, an oft-covered song that stands as one of Numan’s most gothic outings.

Numan had become a star overnight, despite critical distaste for any music so heavily reliant on synthesizers, and he formed a larger backing band that replaced “Tubeway Army”, keeping Gardiner on bass. “The Pleasure Principle” was released in the fall of 1979 and spawned Numan’s international hit “Cars”, which reached the American Top Ten and hit number one in the UK; the album also became Numan’s second straight British number one. He put together a hugely elaborate, futuristic stage show and went on a money-losing tour, and also began to indulge his hobby as an amateur pilot with his newfound wealth.

Numan returned in the fall of 1980 with “Telekon”, his third straight chart-topping album in Britain, and scored two Top Ten hits with “We Are Glass” and “I Die: You Die”; “This Wreckage” later reached the Top 20.

In 1981, Numan announced his retirement from live performance, playing several farewell concerts just prior to the release of “Dance”. While “Dance” and its lead single, “She’s Got Claws”, were both climbing into the British Top Ten, Numan attempted to fly around the world, but in a bizarre twist was arrested in India on suspicion of spying and smuggling. The charges were dropped, although authorities confiscated his plane. His retirement proved short-lived, but when he returned in 1982 with “I, Assassin”, some of his popularity had dissipated - perhaps because of the retirement announcement, perhaps because the charts were overflowing with synthpop, much of which was already expanding on Numan’s early innovations (which were starting to sound repetitive). “I, Assassin” was another Top Ten album, and “We Take Mystery (to Bed)” another major hit, but in general Numan’s singles were starting to slip on the charts; the title track of 1983’s “Warriors” became his last British Top Twenty hit (excluding reissues and collaborations).

Numan and Beggars Banquet subsequently parted ways, and Numan formed his own Numa label, kicking things off with “Berserker” in late 1984. Sadly, longtime collaborator “Paul Gardiner” died earlier that year from a drug overdose. 1985’s “The Fury” became the final Numan album to reach the British Top 30. Over the next few years, Numan collaborated occasionally with “Shakatak’s” Bill Sharpe, releasing four singles and one album from 1985-1989.

Following 1986’s “Strange Charm”, Numan signed with IRS, but the relationship was fraught with discord from the start. IRS forced Numan to change the title of 1988’s “Metal Rhythm” to “New Anger” for his first North American release since 1981 (and also remixed several tracks), refused to release his soundtrack for the film “The Unborn”, and would not fund any supporting tours for “New Anger” or 1991’s “Outland”. When his contract expired, Numan returned to Numa for 1992’s “Machine + Soul”.

1994 brought the release of the industrial-tinged “Sacrifice”, the first glimmering of Numan’s return to critical favor and underground hipness. Over the next few years, bands like “Hole”, “The Foo Fighters”, and “Smashing Pumpkins” covered Numan songs in concert, and Marilyn Manson recorded “Down In The Park” for the B-side of the “Lunchbox” single; moreover, “Nine Inch Nails” cited Numan as an important influence. With his fan base refreshed and expectations raised, Numan delved deeper into gothic, metal-tinged industrial dance on 1997’s “Exile”. However, he didn’t truly hit his stride in this newly adopted style until 2000’s “Pure”, which was acclaimed as his best work in years and expanded his cult following into new territory.

In 2003, Numan enjoyed fleeting chart success once again with the “Gary Numan vs Rico” single “Crazier”, reaching No.13 in the U.K. chart. Rico, who is an up and coming artist from Glasgow, also worked on the remix album “Hybrid” which featured reworkings of older songs in a more contemporary industrial style. In 2004 Numan took control of his own business affairs again, launching the label Mortal Records and releasing a series of live DVDs as a precursor to his highly anticipated new studio album, “Jagged” which was released on 13 March 2006. An album launch gig took place at “The Forum, London” on 18 March 2006. Numan announced a UK tour commencing in April 2006 and plans to tour other countries, including the USA, during the year in support of the release. Numan also to launched a “Jagged” website to showcase the new album.

Numan contributed vocals to four tracks on the April 2007 release of Ade Fenton’s debut solo album “Artificial Perfect” on his new industrial/electronic label Submission, including songs “The Leather Sea”, “Slide Away”, “Recall” and the first single to be taken from the album, “Healing”. The second single to be released in the UK was “The Leather Sea” on July 30, 2007.

In 2008, he released a double CD remix album “Jagged Edge”, based around 2006’s critically acclaimed “Jagged”, co-produced with Ade Fenton. The pair are currently in the studio working on Numan’s 18th studio album “Splinter”, due for release in 2009.

While Numan is known for his electronic music innovations, he prefers real instruments. He explained in an interview with Songfacts: “I didn’t go the technology route wholeheartedly, the way Kraftwerk had done. I considered it to be a layer. I added to what we already had, and I wanted to merge that. There’s plenty of things about guitar players, and bass players, and songs I really love that I didn’t particularly want to get rid of. The only time I did get rid of guitars was on Pleasure Principle, and that was in fact a reaction to the press. I got a huge amount of hostility from the British press, particularly, when I first became successful. And Pleasure Principle was the first album I made after that success happened. I became successful in the early part of ‘79 and Pleasure Principle came out in the end of ‘79, in the UK, anyway. And there was a lot of talk about electronic music being cold and weak and all that sort of stuff. So I made Pleasure Principle to try to prove a point, that you could make a contemporary album that didn’t have guitar in it, but still had enough power and would stand up well. That’s the only reason that album didn’t have guitar in it. But apart from that one album they’ve all had guitars - that was the blueprint.”